Photos provided by Aina Eriksson.

Every month, the Agam Agenda shares a letter from someone in our team: a personal message toward shaping kinder futures. Read the letter for February 2023 by Aina Eriksson, our writer.

My homes are two starkly different places.

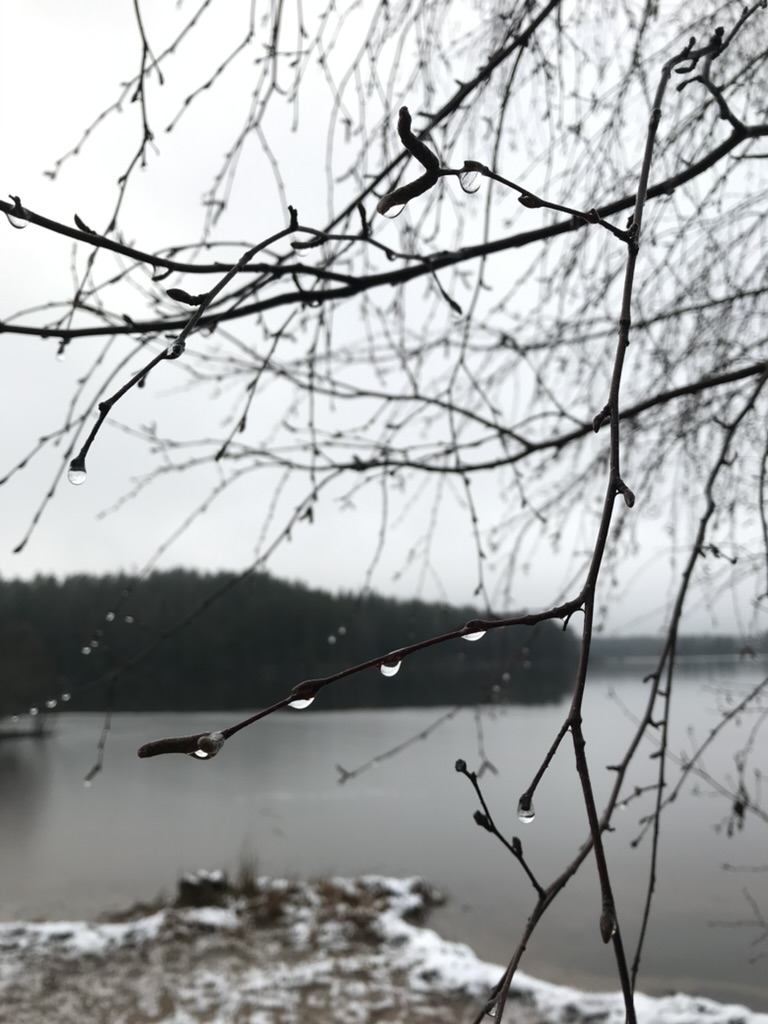

One, located in the uplands of northern Philippines, is humid, moist and mountainous. The other, buried in the vast pine woodlands of central Sweden, is dry, crisp, and fresh. In Sweden most of the year is spent by watching the seasons change. My farmor (paternal grandmother) would often say how she loved spring. Aside from the budding trees and flowers she would describe how the spring light was her favorite part—“shy, pale white, and dull”. Having spent most of the Swedish winters in the Philippines, I couldn’t understand how a dull and shy sun could be so enthralling to her.

I noticed how her generation would spend hours sitting by the window, staring into what seemed like nothingness to an eight-year old child. I remember that their passivity and old age saddened me, and I’d hurry to find distractions to escape the melancholy that levitated around them.

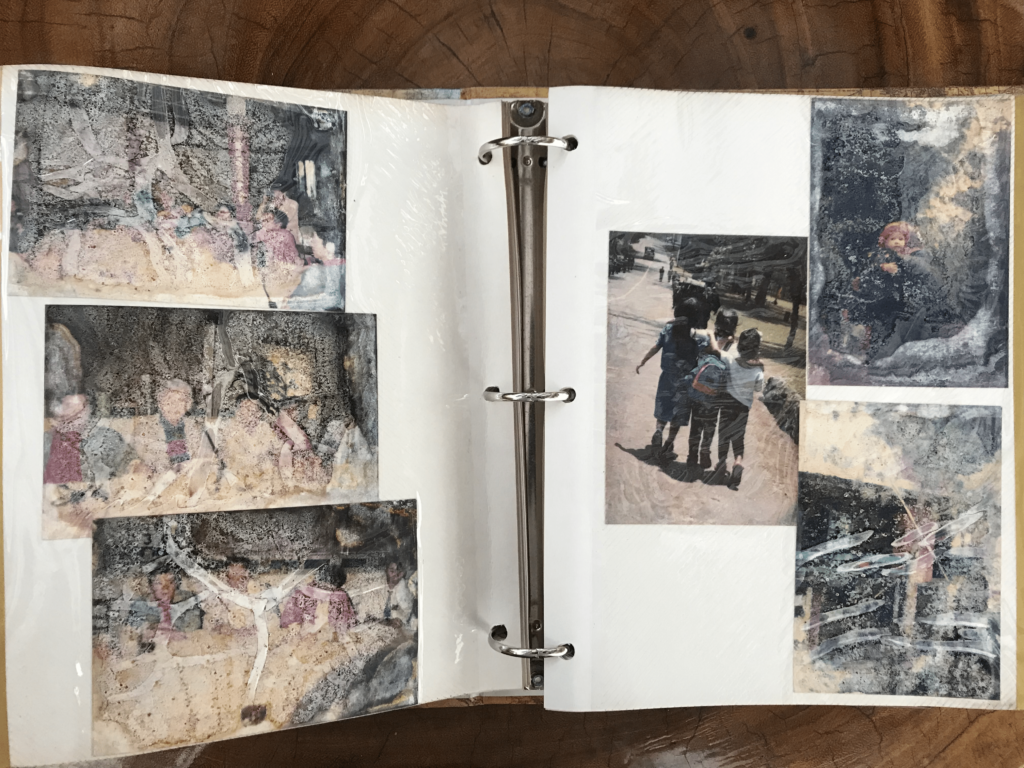

In my Filipino home I’d find a similar sadness. But there it was found in the decaying corners of my wooden house. The dispersed holes left behind by termites, the mold that would steadily consume photographs, the musky smell in a room that hadn’t felt the presence of a person in months. In contrast to Sweden, sunset comes quickly in the Philippines, and when the light would change from golden to gray I would turn on all the lights in the house to counter my gloom.

Would paying attention to death help us live beautifully with the discomfort it brings?

I think that the eight-year old me could already feel the presence of death. Without knowing it intellectually—the sun setting, the seasons changing, and time moving on felt like death to me. I knew instinctively, already then, that I could not affect nature’s irreversible momentum, which inevitably leads to the cessation of something.

We live with death, but most of the time our attention and senses are attuned elsewhere. Would paying attention to death help us live beautifully with the discomfort it brings? Death has decided to be my close companion for a year now. And like my eight-year old self, I have found an array of methods to try and make my new seat-mate invisible. In my unsuccessful frenzy for distraction, my body reminds me that the sadness I feel is not new. It takes me back to the memories of dull sunlight in Sweden and the moldy brown ceilings after the rainy season in the Philippines. It reminds me that distraction will not remove my feelings nor will it change the outcome. Perhaps there was a reason why my grandparents sat by their windows and paid close attention to how the light changed with the seasons.

Because of my homes’ climates, change is recorded differently in each place. In my urban Philippine home, change is evidenced in nature’s most silent process: decay.

The plentiful rains coupled with the humidity and abundant sunlight encourage creatures and plants to merge with humans in their cityscapes. In their traversing they make holes, find crevices, and crack open surfaces as they journey to survive. Within just a few months, a concrete building may crumble as plants dig their roots into its many sides, and the newly replaced laminated floor has bubbled and is starting to crack. In the Philippines decay is treated as inevitable, and I’ve always been amused by how people get on with their days with full acceptance of the decaying objects in their lives, like the rusty bolt lock that won’t let you secure the bathroom door shut, or the desilvering mirror that only shows you half of your face.

My Filipina mother, who is battling a life-threatening illness, tells me “death is part of life. When we view it this way it isn’t so frightening, and maybe we can find ease by accepting that all beings come and go.” I think about how this approach to death is harvested from daily life here, like how my Filipino family doesn’t make a fuss over photographs or mementos lost to the mold. That vines are allowed to grow although they slowly strangle the trees. And how the slaughtering of a pig at a funeral is observed with full presence and reverence. Letting my mother’s words in, they puncture the cyst of sadness I have been trying to suppress, and death along with the emotions it brings are allowed to flow all over me.

In Sweden, my country home marks change with preservation. The sturdy hundred-year old log houses in my village hold memories of the past perfectly.

Generations of a family can be seen in the hollowed out wooden steps of the staircase. Souvenirs of a century gone by are found in the intricately carved decorations of the roof’s corners. Outdated furnaces that warmed the house and cooked food, explain the many visitors that have left a pattern of scratches on the kitchen floor. Five years after my neighbor died I walked through his fishing cabin. Nets and lures and fishing rods lay exactly as he had left them. There was hardly any dust as the gaps in the walls allowed the winds to pass through, and the dry Nordic climate kept objects from decomposing. Stepping inside that cabin was like traveling through time, but as soon as I stepped outside again I was reminded of how time had indeed moved on.

When my farmor died, these preserved memories were painful. A few years after her death I instead found gratitude for how the climate had saved these memories. I still use her woven bark baskets to collect blueberries and mushrooms in the summer, and her wooden kicksled to get around icy roads in the winter. I’ve explored the lake with the same boat my grandparents used to take my father fishing. The longevity of these objects have become symbols of how life and death are intertwined. They show me how life continues even when death distinguishes itself.

Even when something or someone is taken away, nature gives back. It could be in the weathered but resilient objects that integrate themselves with the climate, or in the soil that has become fertile from the decomposed wooden house that once used to stand there.

Learning from their starkly different climates, my homes have helped me live with death. The practice of quietly witnessing, like my Swedish grandparents did by their windows, has made me attuned to death’s constant presence. And acceptance, like how the mold was allowed to coexist with us in our home in the Philippines, has given me the space to slowly let go of control.

Amidst the uncertainty of life it is easy to submit yourself to sadness. Now I see that the air of melancholy that surrounded my farmor was in fact sincere acknowledgement of what cannot be changed. By giving time to observe death, in all its instances small and big, one will see that the uncertainty of life is also what brings possibility. The death of summer’s leaves is what brings the possibility for new foliage in the spring. I think I will adopt my farmor’s practice and quietly acknowledge life’s momentum, instead of denying it, and I might uncover some more advice from nature.