All photos taken and provided by María Faciolince Martina.

Every month, the Agam Agenda shares a letter from someone in our team: a personal message toward shaping kinder futures. Read the letter for April 2023 by María Faciolince Martina, our Strategist for Creative Mobilization and Partnerships.

At the beginning of a dance workshop, Susana, our teacher, grabs a cherry tomato with her hand and thrusts it in her mouth as she declares: “In our mouth lives a heritage of flavors.” Before warming up our bodies, we are all invited to ‘wake up our mouths’ by rolling a cherry tomato through every corner of our palate, gums, tongue. “The mouth is where we learn the world as babies, it is the beginning of our embodiment”. All of us present, mouths stuffed with red, draw a collective breath. And there I felt it: through my mouth I am entering my body; through this fruit, through these seeds, I am also arriving at the field where this alimento (nourishment, sustenance) was harvested.

My mouth is a portal.

The places we inhabit and inherit, quite literally, live in us. Foods are a particular expression of a territory, and the act of eating them becomes a molecular conversation between one territory and another: our body. In nourishment we find this language of intimacy with our landscapes, a life-sustaining exchange between our bodily and territorial geographies.

Despite engaging in this dialogue since the day we were born, many of us still struggle to recognize the vital continuity between our environments, including those of our ancestors, and our bodies. I know I don’t fully understand this yet; it’s one thing to think about it and another to integrate and embody it.

From the diaspora, food is a way of invoking a territory, of invoking the knowledges carried in how certain foods and plants interact with our body-territories.

Days after this dance workshop, I start unpacking bags after moving homes, again. This ritual is very familiar to me—I’ve been doing this since I remember. As a child of diasporas, the question of home and territorio—the tapestry forged by the interaction of environments, biocultural memories and histories of place-making—is complex. Which one?

Some primary strokes from my cartography: I was born in Kòrsou (Curaçao), the ‘Dutch Caribbean’, as a daughter of (mostly) Colombian parents whose lineages remember various Atlantic crossings, then was raised in yet a few other places, including some in Europe, whose Mediterranean coast in Catalunya I now find myself rooting on. This life-journey means I often feel I have several bodies that have inhabited several territorios (sometimes simultaneously). I feel held by many waters and lands, yet never ‘at home’ in just one. There’s such real, everyday difficulty involved in handling, in rooting, this plurality. But that also makes me a student of them all.

In this new Mediterranean nido (nest), I cleanse the air, unfold textiles and prints, and assemble an altar. I make and remake a home out of fragments, fragments of all the places that live in me. I carefully take out tamarind and barba di jonkuman seeds from Curaçao, huayruro and chontaduro seeds from the Amazon, several types of beans and maíz from the Andean regions of Colombia. Before me is my ‘traveling homeland’. Susana’s reflections echo through my mind—perhaps there are embodied practices of connection that I do, that we all do already, without recognizing them?

Cuerpo-territorio is a basic relationship used to map violences and direct visions for collective healing, from which the health and liberation of our lands mirror the health and liberation of our bodies.

Amid a series of movements and migrations, to make a habitat responds to a deep hunger for connection. The practice of collecting seeds, flowers, soils, from all of the various territories that have marked my life journey is something I’ve always done. They remind me of what grows, of what gives. To take a pod, and bring it into my own personal ‘seed bank’ is a reminder of my Earth relations and of the places I want to be in reciprocity with. It is a reminder of the sacred webs I am part of, despite the feelings of dis-place-ment. It is a reminder of what a Wayúu ouutsü (healer) from the community of Tamaquito II in La Guajira, Colombia, taught me about her waimaro seeds which she carried after being displaced by coal mining: seeds offer spiritual nourishment, not just nutrition. I am beginning to really reflect that I, too, embody the elements that weave the fabric of our landscapes.

My mouth is a teacher.

There are many ideas or phrases that resonate with me before I can even grasp them. Ideas that feel necessary and challenging, that ask for deep time and commitment to learn to embody them. The notion of cuerpo-territorio (body-territory) has been accompanying and stretching me for years, after first encountering it in engagement with Mesoamerican communitarian feminists who refer to our body as the first territory, and the territory (/Earth) as an extension of our bodies. Cuerpo-territorio is a basic relationship used to map violences and direct visions for collective healing, from which the health and liberation of our lands mirror the health and liberation of our bodies.

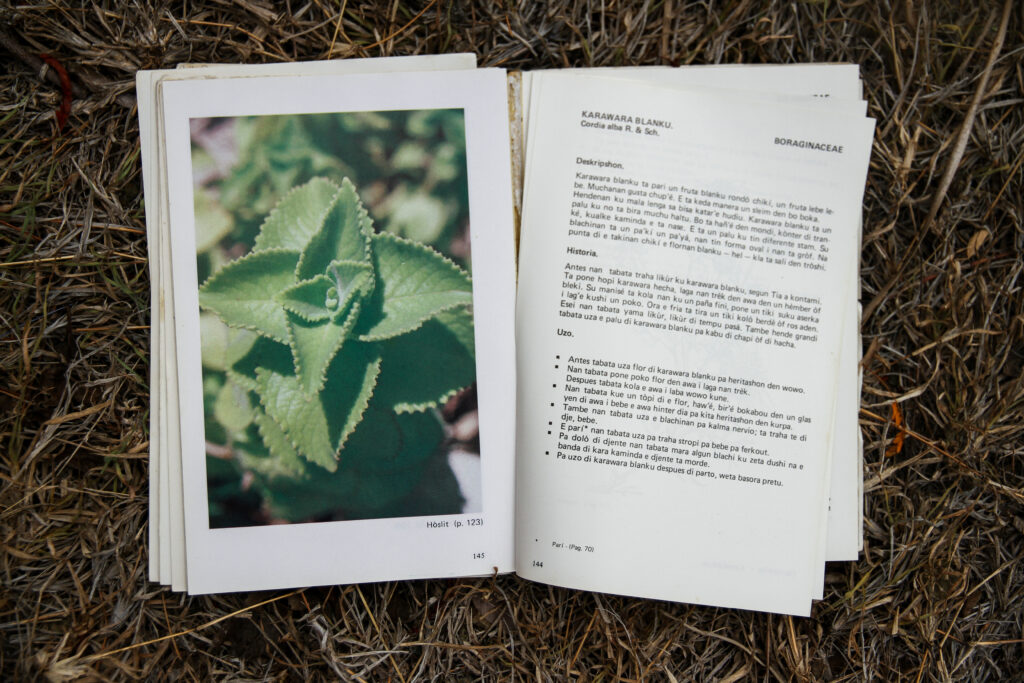

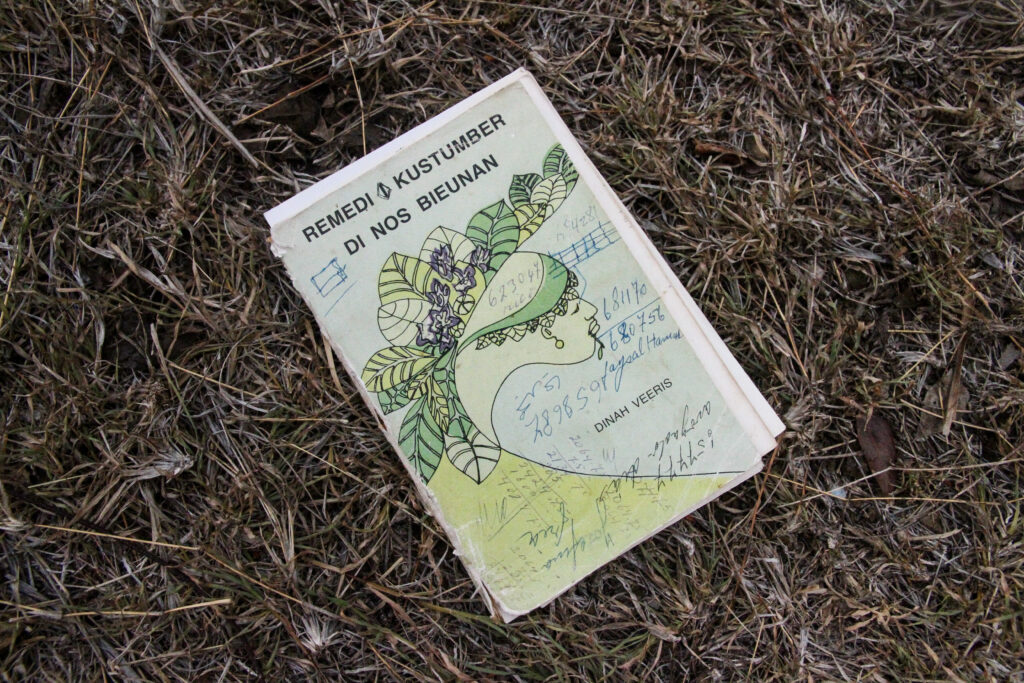

This fundamental linkage makes safeguarding ecological knowledges and foodways essential to the health of territories and bodies. The labor of recovering native seeds, local and ancestral recipes, and plant knowledges is the work of recovering relationships and reweaving cultures of belonging. It is place-based medicine. I’m deeply moved by the ‘agro-resistance’ of setting up local food gardens and seed banks, reclaiming ancestral practices and recipes, to continue sowing, harvesting and cooking food that heals and dignifies. Collectives such as Futuros Indígenas connect cultural heritage and territorial defense in Abya Yala in their Recetario de resistencias (Cookbook of Resistances), where they “compile dialogues and knowledges of our peoples through food, demonstrating acts of food sovereignty with traditional recipes, as well as the recovery of medicinal foods that heal us.” Honoring and protecting the gifts of the earth is a thick braid; it is a cultural, spiritual, and political project.

What does this look like for us who inhabit lands different to those we inherited? From the diaspora, food is a way of invoking a territory, of invoking the knowledges carried in how certain foods and plants interact with our body-territories. The mouth is a portal and food is a bridge back home(s). In addition to collecting seeds, I’ve also remade home through flavor: cooking patacones, arepas, yuca, okra, funchi; relying on karni stobá, sancocho and ayaka for spiritual nourishment. The heritage of flavors that lives in my mouth is generational memory, and also a core expression of my plural identity. But I’m also presented with yet another challenge: how can I honor both where I come from, and where I am now, in my traditions?

Fellow daughters entre mundos, living in hyphenated places, continue to teach me. Recently, I came across the work of Claudia Serrato, an Indigenous Mexican culinary anthropologist living in California, grappling with this question with a lot of wisdom and humility. Something she reflected on stuck with me: “I began to understand the importance of eating what the land here provides for me. It’s a way that the land is offering its gifts… I understand that not only am I a mobile geography, and not only are my taste memories mobile, but I’m also residing in Tongva, Los Angeles, and so I honor that through my foodways. I honor that through the seasons. I honor that through how I rehomed some of the ancestral plant relatives in my home space.”

My mouth remakes home.

I started writing this letter looking out from a train through rural Catalunya, heading to my new nido. Through the window, I see food gardens and plots of huertos peppered across the landscape, seedlings trying to grow amid a brutal drought. In a time of ecological breakdown, of droughts and fires, how can we all honor the places that nourish us? How do we feed what feeds us, how do we grow what grows us?

Mi boca es un campo fecundo.