Details from a mural in Guiuan, Eastern Visayas, painted by local artists after a knowledge sharing session on climate change and local impacts. Photos by Alex Llado.

By Aina Eriksson

February is National Arts Month in the Philippines. Throughout the country, a range of exhibits, performances, and lectures are organized together with schools to showcase the accomplishments coming from each of the seven art forms in the Philippines (architecture, cinema, dance, dramatic arts, literary arts, music, and visual arts). In its 33rd year of celebration, National Arts Month is dedicated to spreading awareness and appreciation for Philippine arts and culture, calling attention to how they contribute to the development of the nation and its people.

In Agam Agenda’s work, art plays a central role in social change, climate activism, and personal expression. Art as a multidimensional approach provides a dynamic and powerful platform to engage audiences and communicate in plural ways. Globally, we are seeing more and more crossovers flourishing: art present at policy conferences, cause-oriented organizations collaborating with artists, and artists themselves using their practice as a way to participate in climate conversations.

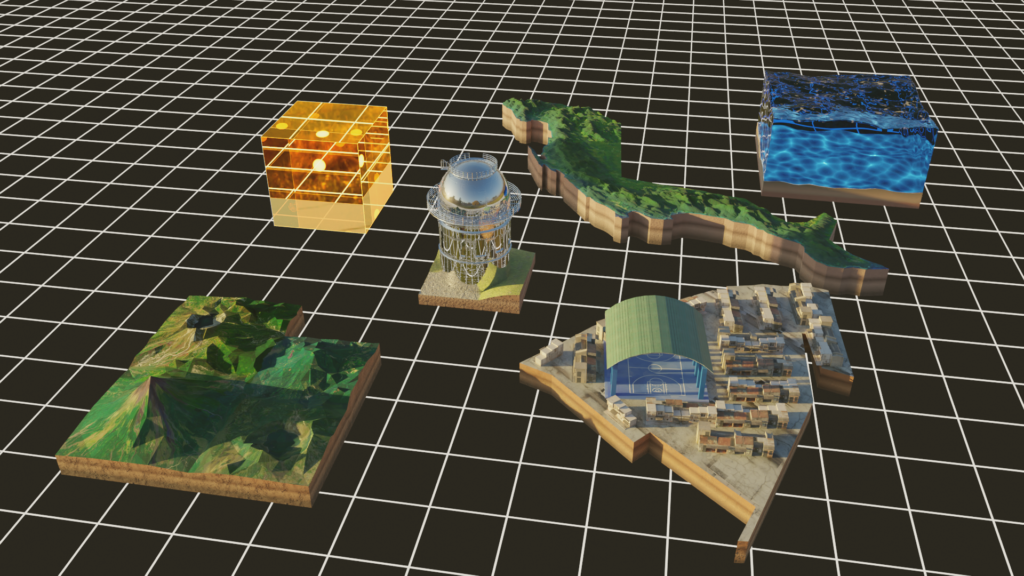

Images taken from Tropical Climate Forensics – Courtesy of MCAD

… the arts provide highly valuable, yet often overlooked, contributions to climate action and knowledge bases for social change.

We already know that art is a mighty communication tool. But going further, the arts provide highly valuable, yet often overlooked, contributions to climate action and knowledge bases for social change. Taking a look at the work of a few Filipino artists we can harvest insights on the power of arts in shaping our world.

Art as investigation and re-presentation

In policy arenas, artists who integrate environmental issues into their work are steadily gaining attention. Many of them use their art as a way to connect local stories and realities with global issues and debates. In the vast archives of scientific reports, statistics, and global predictions, the climate crisis is easily objectified and made distant. Creative storytelling is a way to provide nuanced, empirical, and multimodal representations of the various issues entangled with climate breakdown—representations that are rich in imagery and contemplation, as well as scientific rigor in many cases.

Martha Atienza, Filipino-Dutch artist working with film, brings the realities of the coastal community of Bantayan Island to audiences across the world. In her work Our Islands, a looped film of one minute and twelve seconds shows a procession of Philippine icons submerged under water walking slowly against a current. Seeing the icons submerged alludes to a foreboding future for both Filipinos and others watching this piece. This portrayal signals the facts, that sea-levels are rising and that communities will be lost (along with their cultures, languages, historical memories), but adds another layer of reflection.

By collaborating with the locals of Bantayan Islands the film also presents the enormous skill of the Bantayan men whose lives are deeply connected with their environment, and are able to walk on the seafloor, which they’ve learned through the dangerous practice of hose diving. This layered representation of the imagined future (a submerged nation) with the present day reality (bodies shaped by the sea) connects time/temporalities in our felt and imagined understandings of a changing climate.

Art, beyond any creative output, is a process which enables collective learning.

In another piece, Equation of State, Atienza depicts the decay of Bantayan Island brought about by the intersections of poverty and the drastically changing climate through another looped film. Surrounding the video installation are 19 mangrove plants whose movements are mechanically manipulated to mimic the movement of the tides. Alongside images of deterioration are the steadfast inhabitants of the coast (both plant and human) that brave the hardships using solutions born from their ingenuity. Atienza’s merging of local realities with global issues, and persons with environments in visual form, allows us to witness real stories in multisensorial formats.

We see in Atienza’s work that through her cinematographic practices, she engages in many dimensions of a changing climate: the people affected, materials, and textures of an environment in transformation, the new colors and movements of the sea, among others, deemed important to understanding how Bantayan Island is experiencing the climate crisis.

Art as translation and embodied learning

Art, beyond any creative output, is a process which enables collective learning. In the coastal community of Guiuan, in Eastern Visayas in the Philippines, a knowledge sharing session brought together high school students, artists, climate scientists, and local government officials. The Rig-on Klima Eskwela (Climate School) was organized by The Climate Reality Project Philippines in collaboration with the local government of Guiuan and the Climate Finance and Governance Team and Agam Agenda of the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC). The scientists and government representatives shared the larger picture of climate change, rooted in national data and scientific research, while the high school students and artists shared observations of their changing homes.

After the discussion, the students and artists were given materials to creatively express what they had collected from a day of co-learning. Giving space to both the facts and the feelings, in conversation with their own personal experiences, allowed the students to consider complex concepts like ‘climate resilience’, ‘symbiosis’, ‘regeneration’ and ‘climate adaptation’ from several viewpoints.

These murals were painted by artists Alex Llado, Jeremy Eloberio, and Kieffer Vicuña in the coastal community of Guiuan, Philippines. Photos © 2022 Alex Llado.

Moving between scientific research and embodied experiences gives us a chance to learn differently.

In his work Tropical Climate Forensics, Filipino artist Derek Tumala gives us a great example of the translating powers of art. Taking atmospheric data and future predictions through a collaboration with Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MCAD) Manila, Tumala has made a 3D diorama which allows viewers to move back and forth in time to witness how extreme weather changes have affected the country. By translating scientific research into a virtual experience, audiences are able to visualize, feel and move with the changing climate—transforming the learning experience from the distance of facts and numbers to a close encounter and immersive bodily experience.

Art as a site of knowledge

Artistic practices allow us both to expand our understandings of the climate crisis—its embodied experience, and connections between local and global realities—and to engage in an exercise of collective knowledge production and response-ability. With this approach, the arts are sites of knowledge, where creative inquiry uncovers possible realities, creates new vocabularies, and connects different narratives.

Given that the climate crisis encompasses all dimensions of life on Earth, from social to cultural and ecological, our strategies to confront its challenges will need to be diverse and many. Part of the work will be creating new imaginaries for our futures which will rely on the multiplicity of perspectives. If we treat the arts as a site of knowledge and integrate them into climate action—not just as communication tools, but also applying their process and perspectives to climate work—then the pool of resources to tackle, solve, and heal from the climate crisis expands.

Editor’s note

Agam Agenda’s op-eds trace the connections between the arts, culture, and climate action. Recognizing equally the importance of the humanities in building resilient communities and the current inadequacy of its integration in climate policy negotiations, Agam Agenda strives to demonstrate the integral role the humanities play in climate policy. This piece is written by Aina Eriksson who is a development communicator working as a writer at the Agam Agenda.