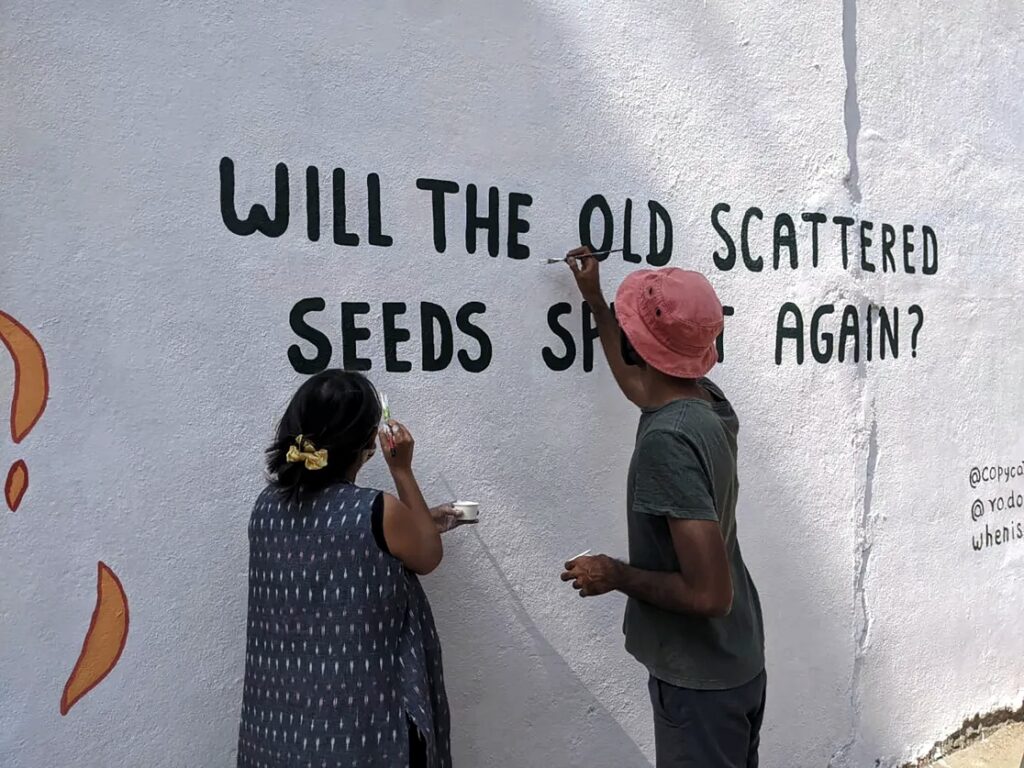

Mural in Jogjakarta, Indonesia, painted by local artists Tamarra and Bodhi IA, in collaboration with the Agam Agenda. Lines used in the mural are from a poem written by African feminist and writer Malebo Sephodi. Photo by Tamarra.

By Carissa Pobre

We live in troubled times, we like to say. In these times when the experiences and crises of fear, anxiety, depression, and grief are so widespread, we turn to ‘each other’: the animate forces that can hold us in our emotions, and help us make sense of a troubled world.

If the global pandemic was any indication of this at scale, it is creativity and its processes that can hold us in what is essentially a collective struggle: of navigating challenges that upend and usually expose what’s outside of our limited control. People do the best they can in their search for survival and meaning (and the two can be mutually exclusive)—inclining ourselves towards the possibility that, somehow, we could change our circumstances. It’s what makes these times so fragile, and what speaks to our humanity.

In this regard, creativity is an enabling force that revitalizes our agency and human consciousness. It grants us the ability to see possibilities beyond personal, societal, and ecological turmoil and imagine how we could still pull through. Inside of the raw ‘feeling-states’—of anxiety, sadness, joy and euphoria too—are rigorous cultural, political, and spiritual questions lodged within them. How do we create futures that are kinder and more compassionate? How can we truly listen to and love one another? How can we resist the ways that the Earth’s and one’s own inner resources are being extracted for accumulating profit and power? Many people turn to a page, a story, an instrument, or a canvas to respond to such complex questions. Engaging in one’s creativity is a way of playing out emotions, as well as the questions lodged in them, that by writing or making art, we tend to a process of creative inquiry.

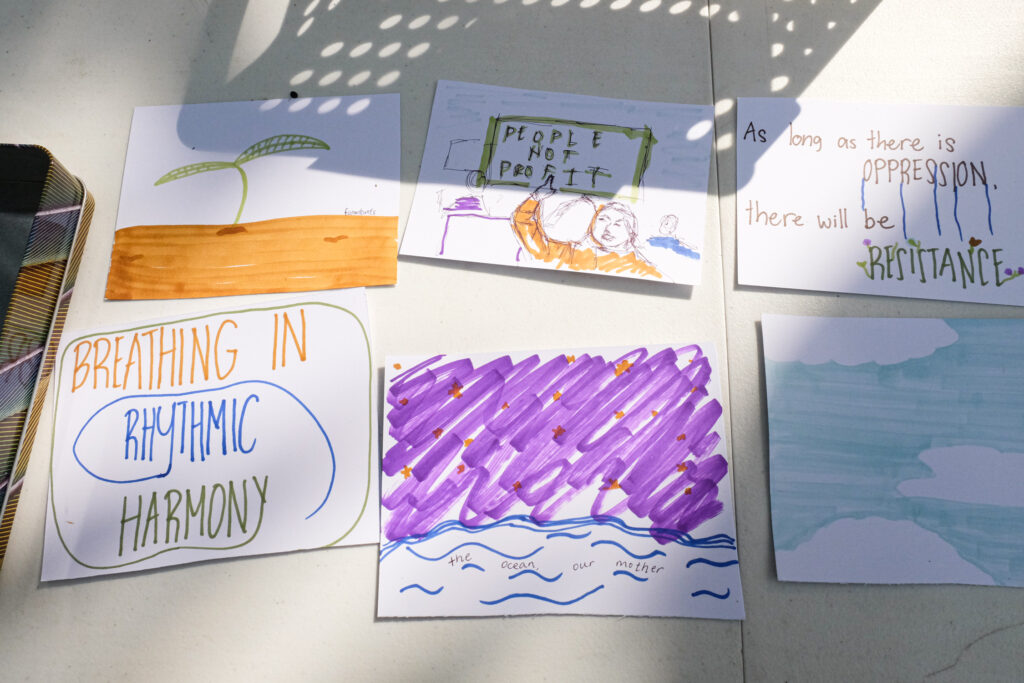

Scenes from a climate action and arts fair in Manila, Philippines, organized by Green Dreams of a Generation, 350Pilipinas, Youth Advocates for Climate Action-Philippines (YACAP), and Agam Agenda, held at the Memorare Manila Monument in November 2022. Photos by AC Dimatatac.

Inside of the raw ‘feeling-states’—of anxiety, sadness, joy and euphoria too—are rigorous cultural, political, and spiritual questions lodged within them.

But the past decades of accelerated, multiple crises have made it hard to live under conditions that nurture this creative process. In fact, we have been living in times when the importance and role of creativity—in imagining alternatives, connecting with people and places, working with difference, inviting joy and rest—are pushed aside from mainstream conversations in favor of quick fixes. Creative modes are tokenized or diminished, especially by spaces of dominant power and decision-making, and perhaps worse relegated to outrightly ‘creative’ or artistic spaces whose outcomes start and end there.

In troubled times, we need conditions in which our human capacity for creative inquiry can be acknowledged and cultivated, in order to constructively respond to and interrogate our current realities. Beyond the often repeated empty phrase of ‘asking people to be more creative’, it is through creative inquiry—which asks questions, confronts assumptions, draws parallels and connections between things that are otherwise seemingly unrelated—that we can awaken our senses and consciousness to something more, and to something else.

When we are compelled to change our conditions, as we are called upon to do now, creativity wagers on what is possible.

Creative inquiry and our shared humanity

The necessity of creative inquiry could not be more urgent than in the climate crisis, precisely because it is a crisis that points to our notions of development and imagination. Can we imagine justice, distributing resources, power and its interplay among various actors? Do we reflect on the stories of history and places that have organized societies? Do our imaginaries include narratives that have long been there, but are still systematically excluded in the machinery of development and sustainability?

If we shift the world-order and ask, Who or what feels pain? Who or what is animate? and interrogate what truly is lost as cost or externality, then we can create conditions that holistically acknowledge the relationships and boundaries which sustain and nourish life.

Lines from a poem by regeneration practitioner Wangũi wa Kamonji being painted on a public mural. Visual artists Rohini Kejriwal and Mayur Nanda aka Copycat Design in Bangalore, India painted a mural in response to the poem. Photos by Rohini Kejriwal.

Such complex questions are ones which rigid modes of inquiry are not equipped to fully examine. Where stringent definitions, technical equivalences, and standardized categories often reinforce systems of consumptive and colonial power, creative inquiry allows us to break them open. When we engage in a creative process, we revise and revitalize what we know: by animating facts with emotions, inquiring into emotions from multiple perspectives, connecting known knowledges with new knowledges, and embracing unknowns that may not meet a particular ‘standard’ way of doing. By admitting what we know and don’t know without capitulating, such a process fosters much more holistic insight into ecological and cultural connections.

Creative inquiry helps us keep these connections and parallels alive, rather than separating our interdependencies. Emboldened by a practice of creative inquiry, the arts then offer us rigorous sites and exchanges of knowledge and possible alternatives. Embracing more open-ended, artistic approaches also involves taking risks, where the stakes are highly personal and political: offering alternatives that ask ourselves and others to unlearn and challenge assumptions and core beliefs. Conversely, the diminishment of creativity in this regard—in climate policymaking, pushing for ‘sustainable solutions’, and educational systems—only serves to strengthen the case for ‘business as usual’.

So many discussions on environmental problems are spaces where people’s experiences and emotions are dismissed, revealing the poverty of care and consciousness.

Photos from the collection of Agam Agenda.

Creative consciousness: the pleasure and wisdom of process

Cultivating creative consciousness rests on allowing and enabling process. Even within arts and culture industries this is not always appreciated, and the co-optation of cultures, stories, and artforms under consumptive and colonial models has made it difficult to appreciate the nature of process—at times downright impossible. The artwork, for instance, is treated merely as an outcome that is then marketed and sold, easily subjected to cycles of production and consumption.

In her widely quoted statement, “We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings”, the science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin contextualized this by stating how books (like other artforms) “are not just commodities. The profit motive often is in conflict with the aims of art.”

Art is rarely, if not at all neutral—that even the white cube of an art gallery, or a dusty old book sitting on our shelves, or a song we hum to ourselves in an idle moment, are telling of a lived experience or a response to social conditions—and thus the existence of all art (in the blunt sense) is almost always political (in the ‘charged’ sense). And we need more of it. Of course it is also true, to borrow the words of Filipina poet Conchitina Cruz (quoted here by fictionist Sigrid Gayangos), that “there is something amiss in collective action if all that comes out of it is more poetry.”

Creative inquiry helps us keep these connections and parallels alive, rather than separating our interdependencies.

At its best, creative play with materials, language, body, and form can be cultivated as processes of inquiry into collective ecological and cultural consciousness. By acknowledging experience, emotion, and expression as viable, vibrant elements in our environmental, social, and political responses, we stand a better chance at healing and repairing relationships on our planet—doing it slowly, trusting the process, being in the present. In the pleasure and wisdom of creative processes, we develop our shared humanity.

At Agam Agenda, we work to center process in this way—particularly through the arts and, more broadly, arts-based strategies and storytelling. This is because so many discussions on environmental and social problems are spaces where people’s experiences and emotions—as evidence of ecological and cultural disconnections—are dismissed, revealing the poverty of care and consciousness which separates us from ourselves, from nature, from each other.

As the poet CAConrad, author of ECODEVIANCE: (Soma)tics for the Future Wilderness and a contributor to the When Is Now creative campaign, helps us see, poetry is one art that can awaken our senses in this way. It is one among such “ancient technologies” that help us become and remain present “to sharper lenses of wakefulness” that we need in such times of crises.

In their creative practice, drawing from rituals and magic, they make a powerful case for how poetry can transform and channel one’s feeling-states into focus. “There is no doubt that misery can provide poetry,” they explain, “but once we realize it is the focus inside the misery that captures our voice, then we can begin to construct (Soma)tic rituals which can handle any subject.”

Part of the challenge then is to “allow poetry to become an integral and necessary part of your life”, as CA offers. And perhaps it is because

—excerpt from when will by CAConrad

Continuing process: a carrier bag theory

In 1986, Ursula K. Le Guin offered a retelling of the story of human evolution, in a beautiful, provocative piece titled The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Instead of the first technology of human civilization being a spear (a weapon of domination, murderous, and phallic too), Le Guin celebrates the theory that the first technologies actually served to gather, collect, and hold what’s useful and meaningful in one’s journeys. For it’s true: “If you haven’t got something to put it in, food will escape you.”

Drawing from the book Women’s Creation: Sexual Evolution and the Shaping of Society which explained how “the first cultural device was probably a recipient”, Le Guin redefines the story of human evolution and the purpose of technology. Rather than making expeditions and extractions to triumph over nature’s ‘uses’, in which humanity is obsessed with fixed resolution (such as techno-fixes) or their lone ascent, human beings engage their environments in a manner that is more curious, open-ended, and shaped by one’s senses and experience—with a carrier bag as our primary tool.

This retelling offers the provocation that what we sense shapes cultures, and thus, the urgent need to cultivate creative inquiry is about (re)awakening our capacity to experience the world and its gifts. By centering the importance of a Carrier Bag in human evolution, Le Guin suggests how the container is both cultural form and process, through which we gather personal and cultural meanings that we care for and yearn to share with others. Its simple function might be a little deceiving, but its ‘technology’ lies in this very wisdom: the process itself.

We do have magical carrier bags which can hold our stories, our emotions, our questions, and together they constellate so many worlds of our Earth’s living cultures.

Medicinal plants and berries foraged during a walk in the Cordilleran town of Sagada, Mountain Province, in the Philippines. The author of this piece took this walk leading to the Bomod-ok Falls in northern Sagada, together with their guide that day, Lorenzo. Photos by Carissa Pobre.

As we go on “gathering wild oats and telling stories” through many landscapes and relationships, we need the tools “that bring the energy home”. We need to reconnect with our humanity through creative modalities in these troubled times. We do have magical carrier bags which can hold our stories, our emotions, our questions, and together they constellate so many worlds of our Earth’s living cultures.

Editor’s note

Agam Agenda’s op-eds trace the connections between the arts, culture, and climate action. This piece is written by Carissa Pobre, a writer, interdisciplinary artist, and creative strategist at the Agam Agenda.