The Agam Agenda, in collaboration with Myska Simty Uta collective and Camino de Wayra medicine house, launched its first cultural festival ‘Fiky Gota’. The seven-color ‘wiphala’ flag is an emblem for many native peoples of the Andes. Photo by Gustavo Mejia.

By Alexandra Walter

According to the Muisca legend, in the Beginning there was only Bague, the Mother Grandmother.

She screamed loud and clear and gods, light, plants, animals, and Muiscas (“the people”) appeared. The gods then filled a pot with seeds and stones and traveled afar and planted the stars and planets. Then they threw the leftover crumbs, and that was the origin of our galaxy and the tiny faraway stars. Everything was beautiful but still;, there was no motion. So the gods visited Bague and she gave them a potion which they drank until they fell asleep. In their visions they could hear the rumor of rivers and waterfalls; the tiger jumped over the deer; the giant trees swayed with singing birds; the Sun rose and a few stars fell off the sky. They could even see the Muiscas carrying on with their daily tasks. When the gods woke up, the golden light bathed the land, and the Sun and the Moon started to spin. [i]

As magical as this may sound, so was my experience when I arrived at the Fiky Gota festival.

Murals were painted on medicine houses at the ‘Fiky Gota’ cultural festival, led by community members of the Myska Simty Uta collective, Camino de Wayra medicine house, and Agam Agenda. Photos by Gustavo Mejia.

I must have arrived after the gods woke up because the whole place was in motion: the muralists painting hummingbirds and jaguars on the walls; the musicians singing and drums and guitars welcoming the newcomers; the fireplace crackling and the kitchen releasing delicious aromas. And surmounting everything, the seven-color wiphala flag scanning the horizon: red representing the visible world; orange, society and culture, and conservation; yellow, energy and force, and human solidarity; white, time, art and history; green, economy and production, and natural resources; blue, space, infinity and the soul; violet, the State and social organizations.

To the sound of a huge conch shell, we greeted the Four Winds, acknowledged the warmth of the Sun and thanked Mother Earth for hosting the encounter. Those around you did not raise their hands to speak, they requested permission to share the word, and at lunchtime we did not eat, we shared nourishment. Without any poise, without an agenda, it just flowed naturally.

Photo (first) by Alexandra Walter. Photos (second and third) by Gustavo Mejia.

We learned about the use of bitter and sweet plants to heal ourselves and others. We planted trees and made offerings to the river. One of the participants explained all the meanings of the Inca Cross or Chakana, the word in Quechua. The Chakana represents the cardinal points of the compass, the three levels of existence (the upper world inhabited by the gods, the world of our everyday existence, and the underworld inhabited by the spirits of the dead). It also represents the Southern Cross constellation.

Photos by Gustavo Mejia.

I did not know anyone in the group, except for Agam Agenda’s María Faciolince, but only through email. And yet everyone was so familiar! There was no pettiness in the embraces, they were long and strong and energizing. As if we all were the children of Bague. Yes, undoubtedly it was a big family reunion.

María, “our” María—who by that time was everybody’s María—then invited us to draw our own interpretation of the Chakana on a big cloth which would then be embroidered by women to put together a big banner that would travel around the world. So we learned about Agam Agenda’s campaign of When Is Now—which by that time also became everybody’s campaign.

Harvest Moon co-editor for Latin America, Alexandra Walter, and Agam Agenda Strategist for Creative Mobilization and Partnerships, María Faciolince, together at the Fiky Gota festival in Colombia. Photos by Gustavo Mejia.

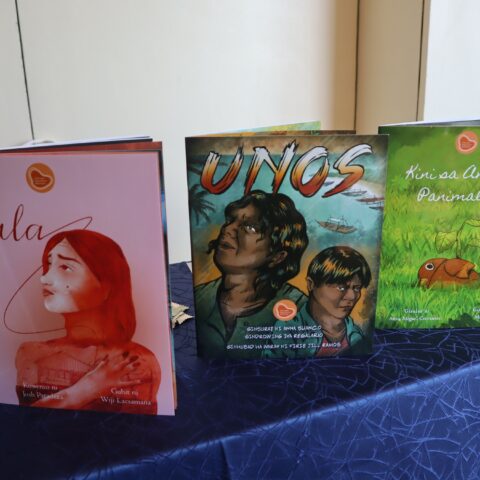

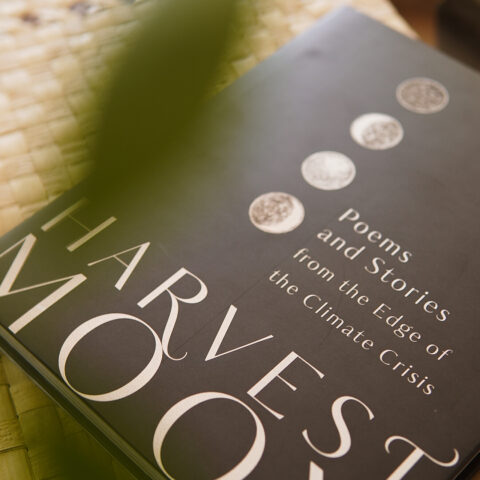

And amidst that environment, I opened Harvest Moon and started reading Irma Pineda’s poem, and people gathered around the fire to listen, and the smoke mixed with the words and with the tears. And the book went around, and the photos went from one hand to the other. It was magical! I am absolutely sure Bague was present.

[i] El sueño de los dioses. Germán Puerta Restrepo